NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Meet the Scientist Studying ‘Fossil Snapshots’ of Ancient Insect Life

Paleobiologist Scott Lakeram analyzes 300-million-year-old coal ball fossils to reveal prehistoric plant-insect interactions frozen in time

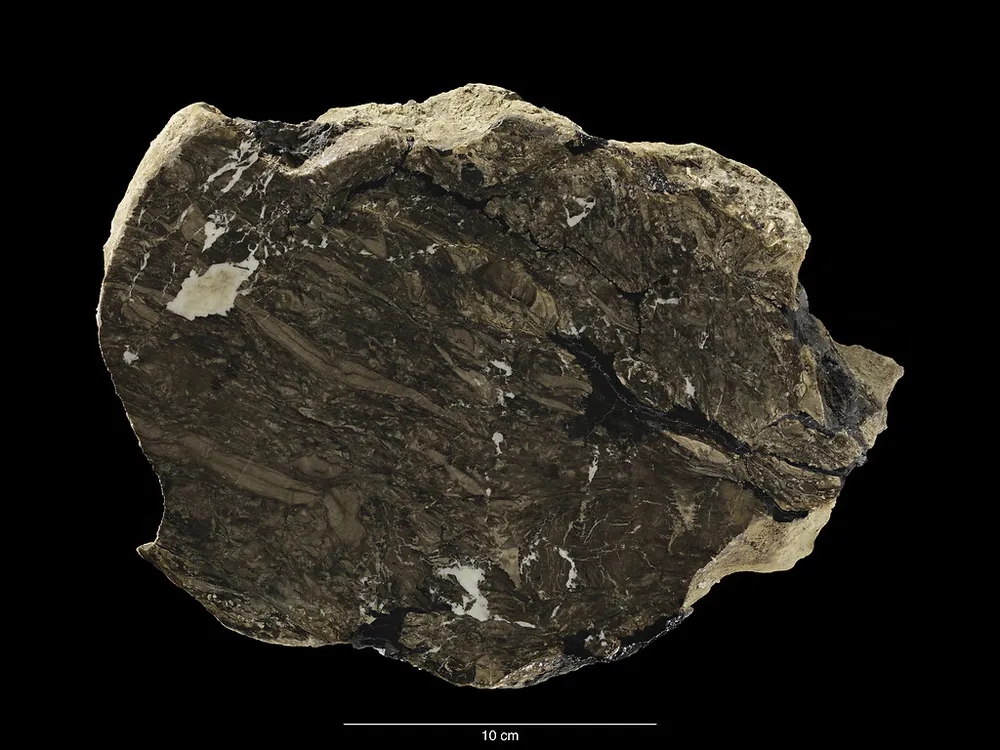

Imagine peering into a tiny, ancient world that existed long before dinosaurs roamed the Earth. Encased within a series of 300-million-year-old coal ball fossils lies an intricate record of ecological interactions. For Scott Lakeram, a paleobiology fellow at the National Museum of Natural History, coal balls are time capsules ripe with insights about the evolution of ancient plants and insects.

During the Pennsylvanian Period, mineral-rich waters flowed through lush peat swamps, preserving pockets of vegetation as fossils. These specimens, known as coal balls, preserve traces of insect burrows, plant fragments and fecal pellets in exquisite detail.

“Coal balls offer a glimpse into the past that is unmatched in the fossil record,” said Lakeram. The National Museum of Natural History holds one of the largest collections of coal balls in the world, with hundreds of specimens hailing from a geologic area known as the Illinois Basin.

As a PhD candidate at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign and a Smithsonian Big Ten paleobiology fellow, Lakeram has spent the last several months analyzing coal balls with high-resolution microscopes. His goal is to reveal the ancient stories hidden within these unique fossils. By reconstructing prehistoric food webs and untangling evolutionary lineages, Lakeram’s research aims to bring long-extinct ecosystems back to life.

What got you interested in paleobiology as a career?

Little kids are fascinated by fossils and the idea of ancient life. I like to say I was one of those kids that just never grew up. My love for the past evolved when I got to college, and I realized I wanted to become a paleontologist. But as a first-generation college student, I had no idea how to break into such a complex field. I eventually took on a project looking at fossilized dinosaur fecal pellets, also known as coprolites. I thought nothing could be cooler than fossilized poop! That project really blossomed my love for this field, and I never looked back.

Now, as a PhD candidate at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign and a paleobiology fellow at NMNH, my research has transformed into what I always hoped it would be. I am looking at plant-insect interactions, specifically within the Pennsylvanian Period using a unique set of fossils called coal balls.

What are coal balls?

Well to start, coal balls aren't actually masses of coal. The name is very contradictory. Coal balls are spheres of plant material that were fossilized over 300 million years ago in the Pennsylvanian Period. These specimens were formed in lush environments with flowing sources of mineral-rich water. The calcium carbonate in the water mineralized around pockets of vegetation and peat, capturing tiny insects and plant life inside. Over time, as the peat was compressed into coal, the pockets of calcium carbonate were protected and preserved for millions of years as fossils. These specimens are snapshots of moments in time that occurred within the upper layers of soil, and they give us access to the ancient world in a way that no other fossils can.

The reason these specimens are called coal balls is because they are found exclusively in coal mines. Thankfully for us scientists, coal balls have no economic value. But they have lots of academic and research value.

What makes coal balls unique in the fossil record, and what can they tell you about early plant-insect interactions?

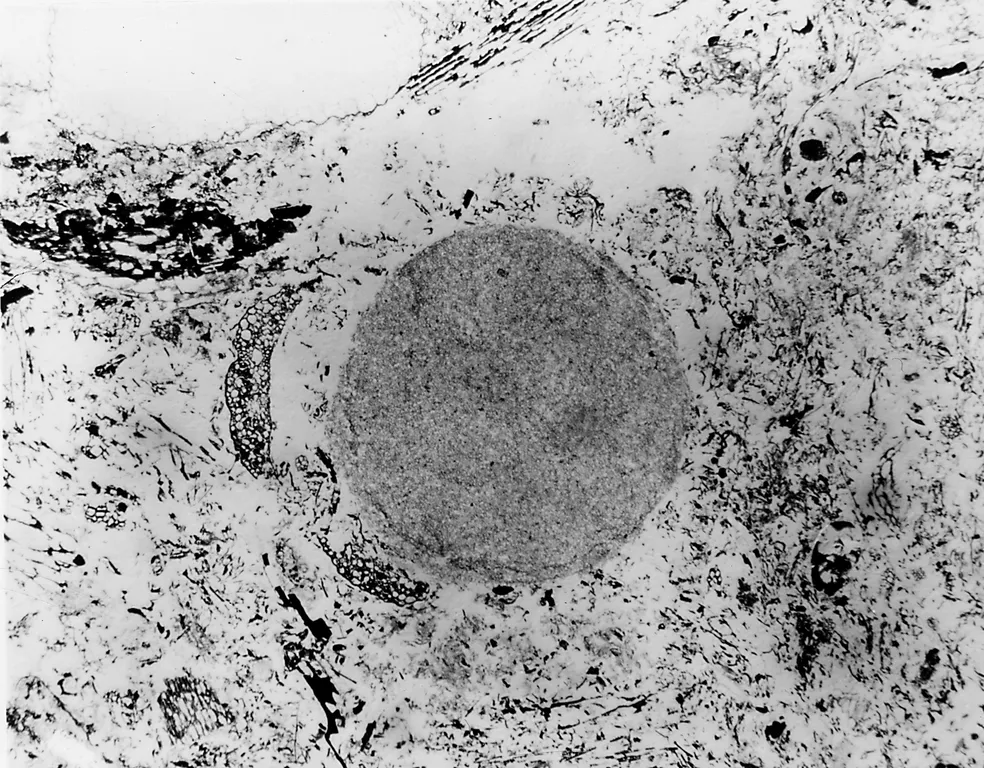

Coal balls are unlike any other assemblage within the fossil record because they give us cellular resolution, allowing us to analyze ancient life in extraordinary detail. Within a coal ball, you could follow every individual cell in a tree branch from the bark to the center pith. This cellular resolution gives us the unique ability to see the upper layers of peat three-dimensionally and build a more complete picture of early environments.

While my research is focused on the ecological interactions between early plants and insects, the one thing we do not get in coal balls is the insects themselves. Exoskeletons do not fossilize in the same way as plant material, so we have to find other ways to identify the impact of early insects on their environments.

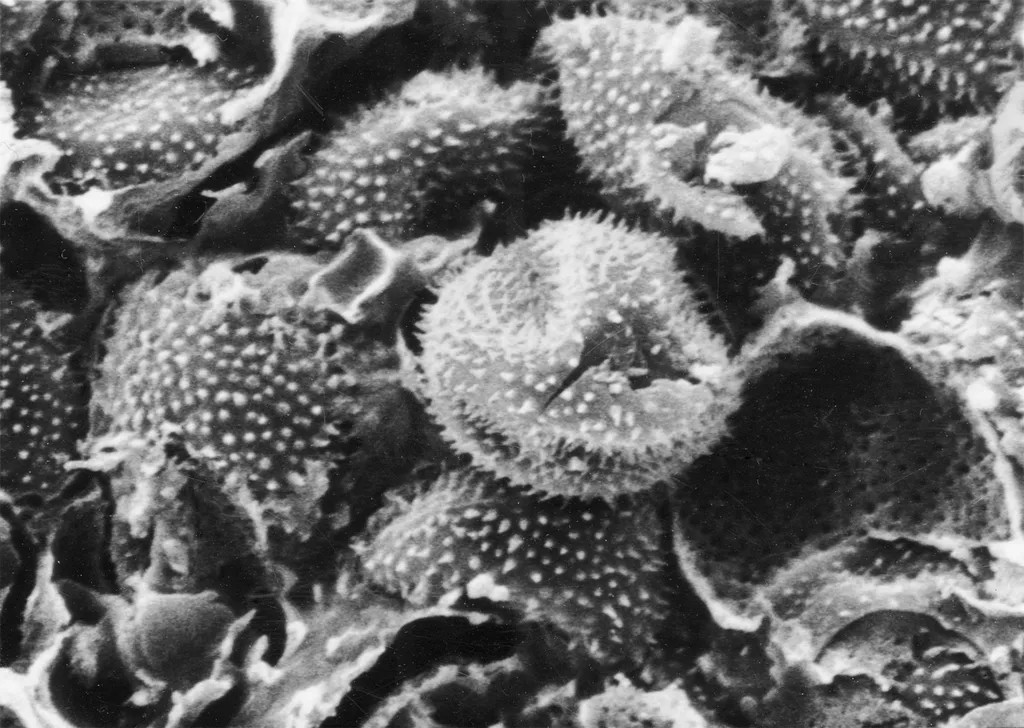

Most coal balls contain fossilized insect fecal pellets. This prehistoric poop retains not only its original size and shape, but also its original contents. Using high magnification scanning technology, we can identify what ancient insects were eating and where. Did a millipede eat through a stem and create a little burrow? Were tiny mites munching through the top layers of soil? Eventually, all of this information will allow me to create food webs linking ancient insects to the plant life around them.

What is the most unusual discovery you have made so far?

One of my most fascinating discoveries within these coal balls was a series of aerial coprolites, essentially flying fecal pellets. While most coprolites look fairly uniform, I was surprised to discover a few that had dry, cracked rinds around them. I realized that these fecal pellets were deposited by insects in mid-flight or as they rested high in a canopy. As the coprolites fell to the surface, they dried out in mid-air, and we can see that 300 million years later. These coal balls can paint us a picture and tell us little stories of what insects were doing in ancient times.

"These specimens are snapshots of moments in time that occurred within the upper layers of soil, and they give us access to the ancient world in a way that no other fossils can."

— Scott Lakeram, paleobiology fellow at the National Museum of Natural History

Discoveries like this have shown me the ecological interactions between early insects and plants seem to have been much more complicated than we previously thought. There were so many feeding behaviors occurring at once, and they were happening everywhere. We can see it in the forest canopy, in the mid-levels, on the ground and even deep under the soil. This time period was teeming with diversity and intricate behaviors that we are only beginning to understand.

What makes coal ball research particularly challenging?

The biggest challenge with this research is trying to figure out what insect species produced each coprolite. Because there are no insect remains preserved in coal balls, I have to get creative in order to identify which species I might be working with. Right now, I am conducting fieldwork in Southern Florida, where I have spent the last month collecting live insects and harvesting their fecal pellets.

When I return to NMNH, I will look at these modern fecal pellets under a microscope to reveal their morphology and anatomy. I am hoping to gauge what the fecal pellets look like in different insect orders, and I will use that research as a modern analog to identify what types of insects may have produced the coprolites in coal balls.

What are your future goals for this research?

My eventual goal is to branch out from this project and look at coal balls from locations around the world. I want to better understand the evolution of insect feeding behaviors over the last 300 million years and discover the ecological niches that drove these transformations.

Unfortunately, studying coal balls is a dying profession and not many people are still researching them. My hope is that I can reinvigorate this field and remind people how much information can be extracted from these fossils. This stuff is so cool. Coal balls may not be as flashy as dinosaur bones, but they are every bit as important. These specimens can help us understand entire plant and insect communities and explain what fundamental ingredients were needed to form the extremely biodiverse environments of the past.

Coal balls are incredible. Looking at one of these specimens is like looking through a window, allowing us to see directly into an ecosystem that existed deep in the history of our planet.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Meet a SI-entist: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is a hub of scientific exploration for hundreds of researchers from around the world. Once a month, we’ll introduce you to a Smithsonian Institution scientist (or SI-entist) and the fascinating work they do behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History.

Related Stories

National Museum of Natural History Scientists Discover That Ancient Insects Perfected Their Plant Palates 165 Million Years Ago

Fearsome Flies: Meet the Scientist Studying the Top Predators in the Insect World

What a Drawerful of Dung Reveals About the Lives of Ground Sloths

Smithsonian Scientists Discover One of the Earliest Mammal Ancestors That Ate Its Veggies