Spring, 1944. Allied forces have taken Sicily and begun the treacherous push up Italy’s boot, but the advance has stalled near the Abbey of Monte Cassino, a historic monastery planted atop a rocky hill in the Apennine Mountains. Using the abbey as an observation post with gun emplacements near its foundation and in the surrounding cliffs, the Germans command the narrow mountain passes of Route 6—the road to Rome.

Allied soldiers take heavy fire as quickly as they can scale the hill. The wounded are passed from one stretcher-bearer to another along hazardous, winding trails before they are loaded into ambulances. As the offensive unfolds, a British Army hospital at Pompeii, the closest large medical facility to the action, is flooded with casualties—soldiers caked in mud and blood, some in shock, others missing limbs. Orderlies unload wounded infantrymen from ambulances and set them down in the courtyard and on the stairs.

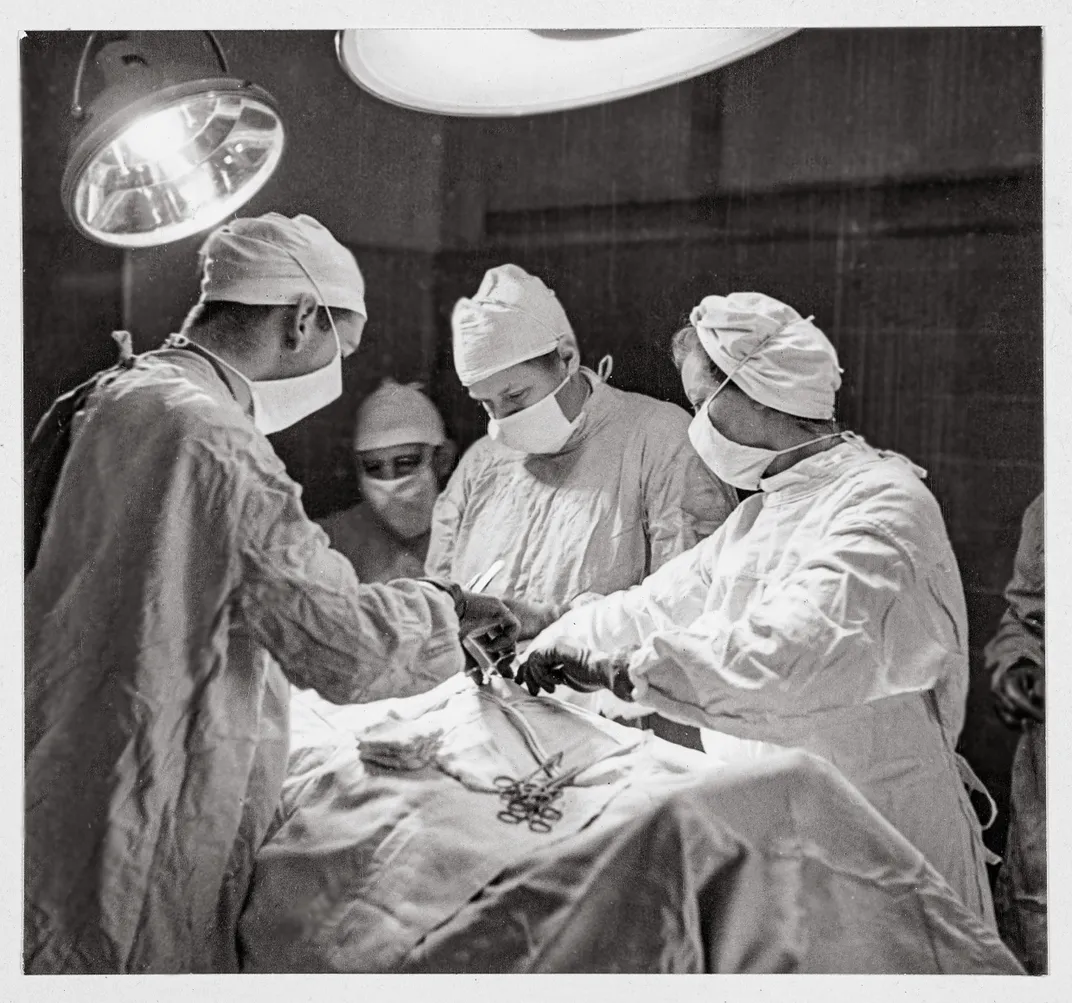

In an operating room, Barbara Stimson, an American orthopedic surgeon, works around the clock—picking out bone shards and shrapnel, suturing gaping wounds, and wrapping shattered limbs in layers of plaster. “We worked hard and fast, for the patients began to pile up in the corridor,” Stimson wrote in letters home, which were later compiled by her sister Dorothy and published in 1987 in a slim volume titled Major Barbara’s Memories of World War II.

By chance, the American photographer Irving Penn, volunteering as an ambulance driver after a heart condition kept him out of combat, encounters Stimson at the hospital. “She is one of the top surgeons, heading an orthopedic unit that does much of the bone surgery for the British in the Italian theater,” he later wrote in a dispatch for Vogue, published in March 1945. “The British have waived their rule about personal publicity because they think Americans should know about her. I do too. She is the real stuff. When I saw her, she had just spent the morning in the operating room. She was white with exhaustion, flecks of blood still on her rubber gloves and apron.”

Penn wrote these lines after a brief meeting, but there is much more of Stimson’s story left to tell. She was indeed a remarkably courageous member of the Allied cause. She also helped open the door for American women physicians to serve in the United States military in World War II and beyond.

Barbara Bartlett Stimson was born in New York in 1898, the youngest of seven children, to the Reverend Henry Albert Stimson, a Congregational minister, and his wife, Alice Wheaton Bartlett Stimson. The family encouraged the pursuit of higher education and public service. Lewis Atterbury Stimson, Barbara’s uncle, trained generations of doctors as a professor of surgery and helped establish Cornell University Medical College. Her cousin, the lawyer and statesman Henry L. Stimson, served in the cabinets of three United States presidents, including that of Franklin D. Roosevelt, as secretary of war during World War II. Barbara’s sister Julia, 17 years older, had served as head of the nursing service for the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I, leading 10,000 Army nurses in aiding the wounded. Her two brothers had also served in the Great War.

“Babbie” was a spirited child who would march up and down the dining room table at suppertime. From a young age she demonstrated a preference for tools over dolls, following her father around the house as he made repairs. He encouraged Stimson’s natural talent by giving her a set of tools at Christmas and arranging for her to take lessons in how to use them. “Father was miles ahead of the rest of the world in an educational philosophy,” she recounted for a profile in the 1947 book Women Doctors Today. “We were never told, ‘You mustn’t do that—it’s only for boys.’” Stimson’s mother also embraced this thinking and “had sworn a little swear that any daughter of hers would do what she wanted to do.”

Both parents were champions of civil rights who supported equal education for women. Barbara attended the all-girls Spence School, in Manhattan, and followed her four sisters to Vassar College, where she majored in chemistry. She made a name for herself as an agile center forward on the hockey team and an outstanding student elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

After graduating from Vassar in 1919, Stimson entered Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons as a member of only the third class to admit women. She graduated with honors in 1923 and secured a surgical internship at Columbia University, where she met William Darrach, a professor of orthopedic surgery. Darrach encouraged her to pursue orthopedic surgery. “I have the hands for it—large, strong, mechanical hands,” Stimson later said in Women Doctors Today. Darrach mentored her throughout her career.

In the 1930s, when less than 5 percent of doctors were female, the idea of a woman wielding hammers and saws to repair the largest bones in the body was unheard of, but Stimson, tall, broad-shouldered and athletic, could handle tools and heavy body parts as well as her male counterparts. She completed her training, joined the Columbia faculty as a member of the newly formed fracture service and became the first woman certified by the American Board of Surgery.

In 1940, as the war in Europe intensified, Stimson, now 42 and with more than a decade of surgical experience, learned that a volunteer group of orthopedic surgeons was organizing to treat war victims in Britain. She submitted an application, only to learn that the only women allowed on the trip would be nurses.

Stimson might never have found her way to the war but for the fact that in early 1941 the British Ministry of Health sent an urgent message to the American Red Cross: Please send 1,000 doctors immediately. As Stimson later wrote, “The number of available doctors had been diminished by capture, by wounding and by death, and the authorities were worried that there would not be enough to take their places.” The United States, however, had just implemented a draft that had swept up almost all available male physicians.

Anxious to find more doctors, the Red Cross turned to physician Esther Lovejoy to identify ten American women physicians to travel to England and serve in Britain’s Emergency Medical Services. Lovejoy, then in her early 70s, had previously worked with the Red Cross to set up hospitals and clinics in France during World War I, staffed by American women doctors who had volunteered after being rejected by the military. She believed prohibiting women from enlisting was a mistake. “It is utterly impossible to leave a large number of well-trained women out of a service in which they belong, for the reason that they won’t stay out,” Lovejoy wrote in Certain Samaritans, her book about the work of the American Women’s Hospitals Service after World War I.

With Britain facing a critical doctor shortage, Lovejoy again swung into action. She sent out questionnaires to the membership of the American Medical Women’s Association and quickly compiled a registry of 2,500 qualified women physicians who were willing to serve in the case of a national emergency. Stimson was among the 500 who had volunteered to work overseas.

Stimson’s questionnaire detailing her extensive surgical training and experience as a fracture specialist who treated injury victims must have stood out, because Lovejoy’s first call in April 1941 went to her. “Dr. Lovejoy wondered if I would like to be considered. I said I would, most definitely,” Stimson recalled in her memoir. When Lovejoy asked Stimson to recommend another woman doctor to go along, Stimson suggested her good friend Achsa Bean, whom she would remain close to, professionally and personally, for the rest of her life.

Unlike Stimson, Bean, a Maine native, was raised in modest circumstances and had taken a meandering path to medicine. She had taught high school, run the town library and worked as a camp counselor before putting herself through the University of Maine, graduating in 1922. After obtaining her master’s degree, she spent six years working for the University of Maine as the dean of women and as an assistant professor of zoology. She finally enrolled in the University of Rochester School of Medicine and graduated in 1936 at age 36. Afterward, she interned in obstetrics and gynecology, and in 1938 Vassar hired her to work in the college health department, where she crossed paths with Stimson, a Vassar trustee. Bean, like Stimson, appeared to have the toughness and resilience required to withstand a war zone.

In July, the women received written instructions including a list of tasks to complete in advance of their departure. Preparing for the trip to England entailed undergoing physicals, getting typhoid immunizations, and having fingerprints and passport photos taken. One of the more challenging tasks was locating winter underwear in August. They visited a department store and found none, but a helpful saleslady phoned nearby shops and located the needed items. Packed and ready to go, the women waited anxiously for word of their departure date.

“We tried to be ‘calm, cool and collected,’ especially with our families, trying to give the impression that crossing the Atlantic with U-boats playing around would be quite interesting and pretending that, of course, Hitler wouldn’t think of invading England,” Stimson later wrote. Finally, at the end of August, after routine background investigations by the FBI and Scotland Yard, Stimson and Bean boarded the Dutch freighter Westland, bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, where it would join a convoy to Liverpool.

The Westland was escorted across the Atlantic by American warships to ward off German U-boat attacks. Aboard ship, Stimson and Bean engaged in lifeboat drills, drew heavy black curtains across windows at dusk and refrained from smoking on deck at night lest a German submarine spot the orange glow of an ember. On the fourth day, Bean burst into their stateroom. “Get up quickly!” she said. “We’re having an ‘incident!’”

The women rushed above deck and saw a warship speeding up alongside the Westland, dropping depth charges along the way. Quick action thwarted the attack, but an unmistakable fact lingered. Though they were miles from England, they had already entered the war zone.

They sailed into the port of Liverpool five days later. “As the Westland moved slowly up the narrow channel, we saw the graveyard of ships: masts, keels, bows, sterns, higgledy-piggledy sticking up out of the water—an unforgettable sight,” Stimson wrote.

Traveling by car through Liverpool, which had been heavily bombed by the Germans, the women saw the city center flattened to rubble, but they also witnessed women with shopping bags making their way through the debris, workmen boarding up windows and merchants sweeping streets. “This gave us our first (but by no means our last) exposure to the calm ‘business as usual’ attitude of the British people,” Stimson wrote home.

She and Bean had hoped to be stationed in the same city, but on their first day of work, Bean boarded a train to the Bristol Royal Infirmary, in the southwest of England, while Stimson squeezed into a packed cabin bound for London to treat civilian orthopedic injuries at the 327-bed Royal Free Hospital. Their separation, however, proved to be brief. The Bristol hospital was expecting Bean to be a male physician, and when it turned out she was not, Bean was promptly driven to London and dropped at the Royal Free Hospital. At the Royal Free, Bean served on the medical wards while Stimson familiarized herself with British surgical practices, working alongside the head orthopedic surgeon. Stimson, an orthopedic trauma specialist, shared her expertise with the use of internal fixation rods to stabilize complex leg fractures and other American surgical techniques.

She and Bean “were both very pleased,” Stimson wrote. “We felt we could be of some much-needed help, both professionally and, in a way, emotionally. We were living, visible proof that Americans cared.”

A few weeks later, eight additional American women physicians arrived to serve in hospitals throughout London. Stimson and Bean socialized with their colleagues regularly. As word of their presence spread, they were welcomed into the homes of socialites and dignitaries who were eager for news from America.

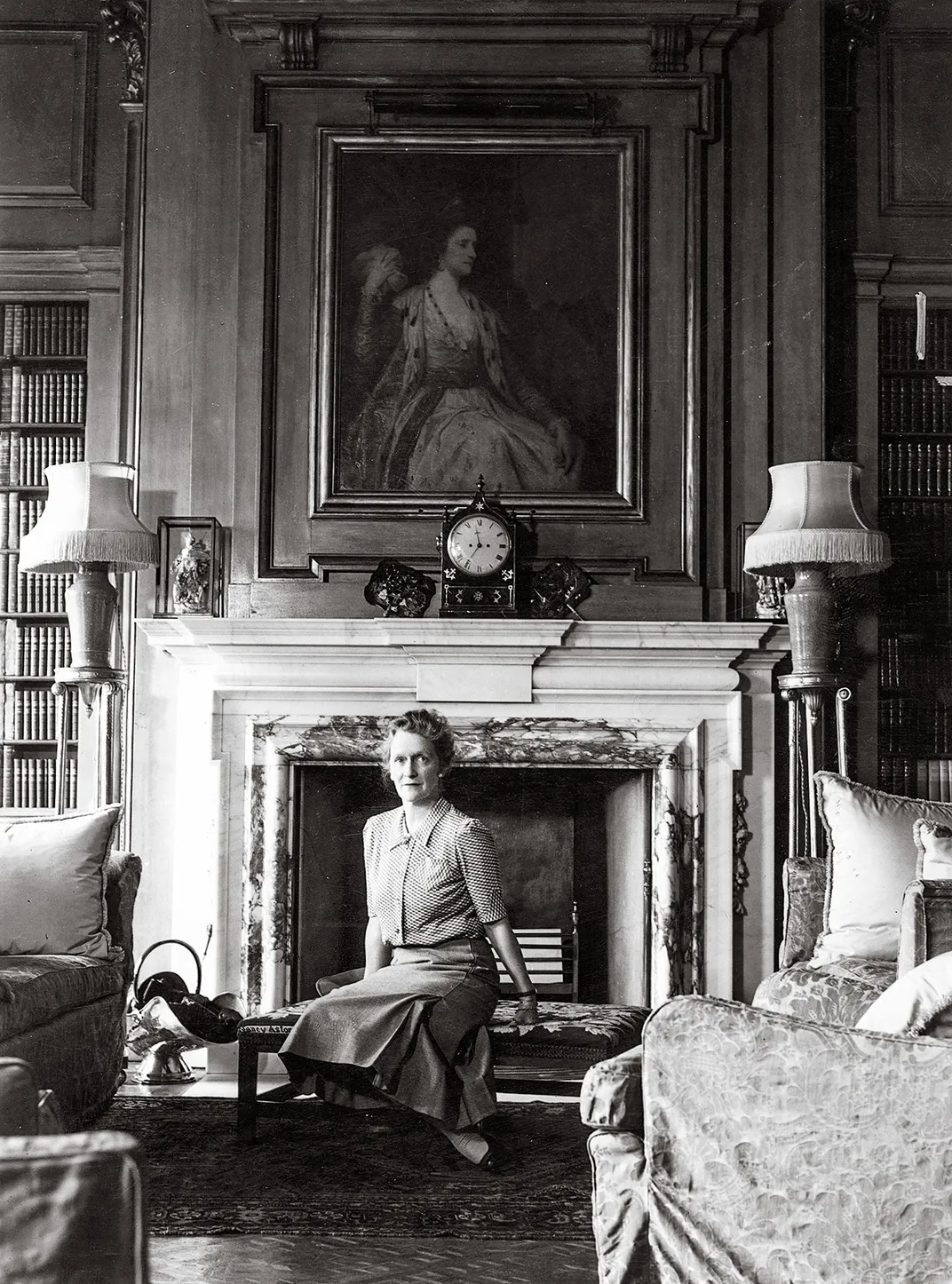

In early December 1941, Stimson, Bean and fellow physician Sarah “Sally” Bowditch accepted an invitation to stay for the weekend at Lady Astor’s country estate, Cliveden House, a magnificent mansion built above the banks of the River Thames. The American-born Lady Astor had moved to England to marry Waldorf Astor, himself an American, raised in England, who became a member of the House of Lords. She too was a pioneer, the first woman seated as a member of Parliament, a position she held from 1919 to 1945.

After dinner on the Sunday night of their visit, an elderly butler tottered into the spacious hall with a small radio that he placed on the dining table. Stimson later recalled the momentous event: “We heard Big Ben strike nine and then ‘Pearl Harbor has been bombed. America is at war!’”

The doctors discussed their plans. Bowditch decided to return to America, but Stimson and Bean preferred to stay in Britain. “We were already 3,000 miles nearer the actual fighting than we would have been had we returned home,” Stimson later wrote. “And as the need for doctors in the British Armed Forces was very great, Dr. Bean and I decided to join the Royal Army Medical Corps [RAMC], if they would have us.”

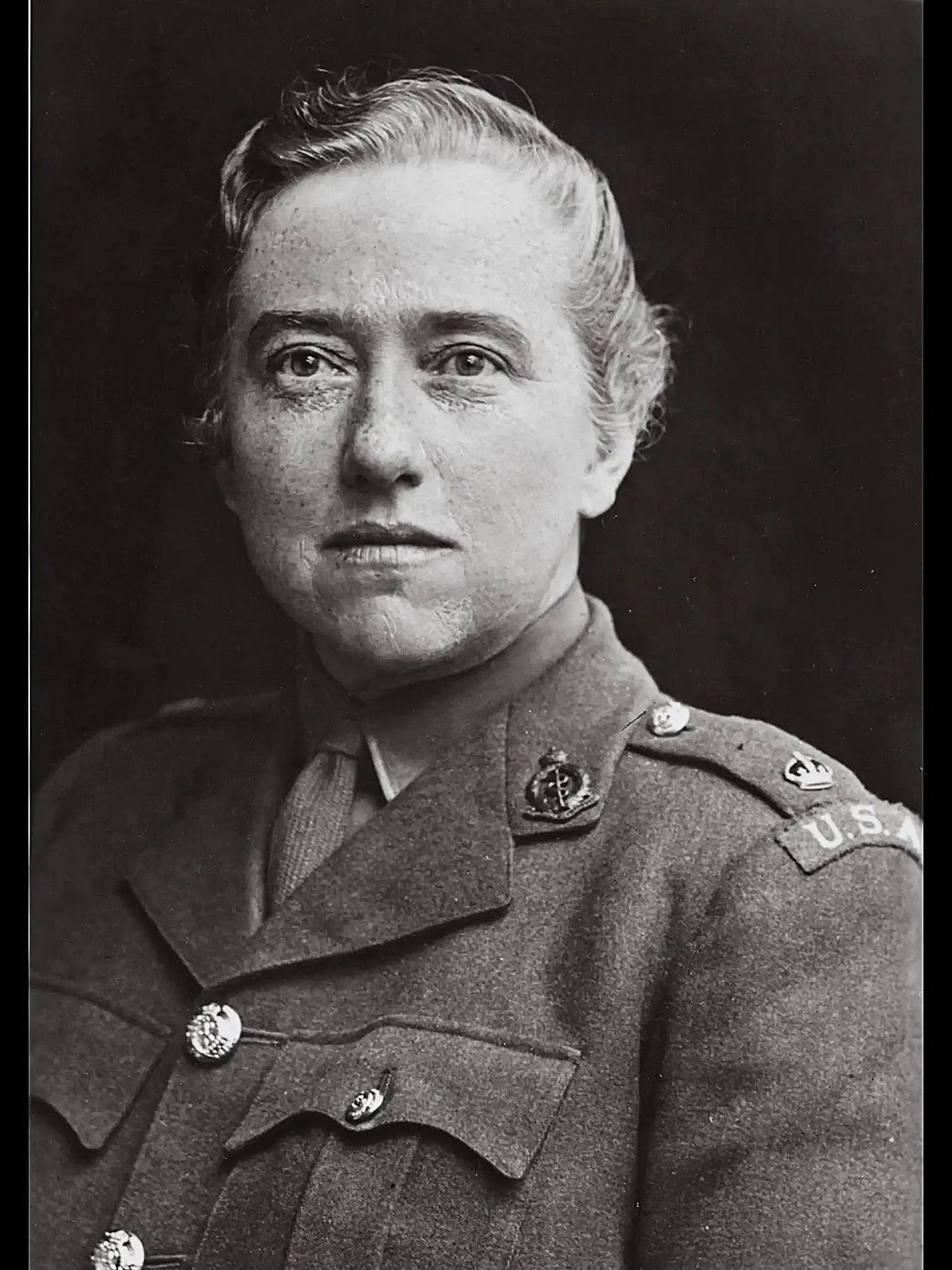

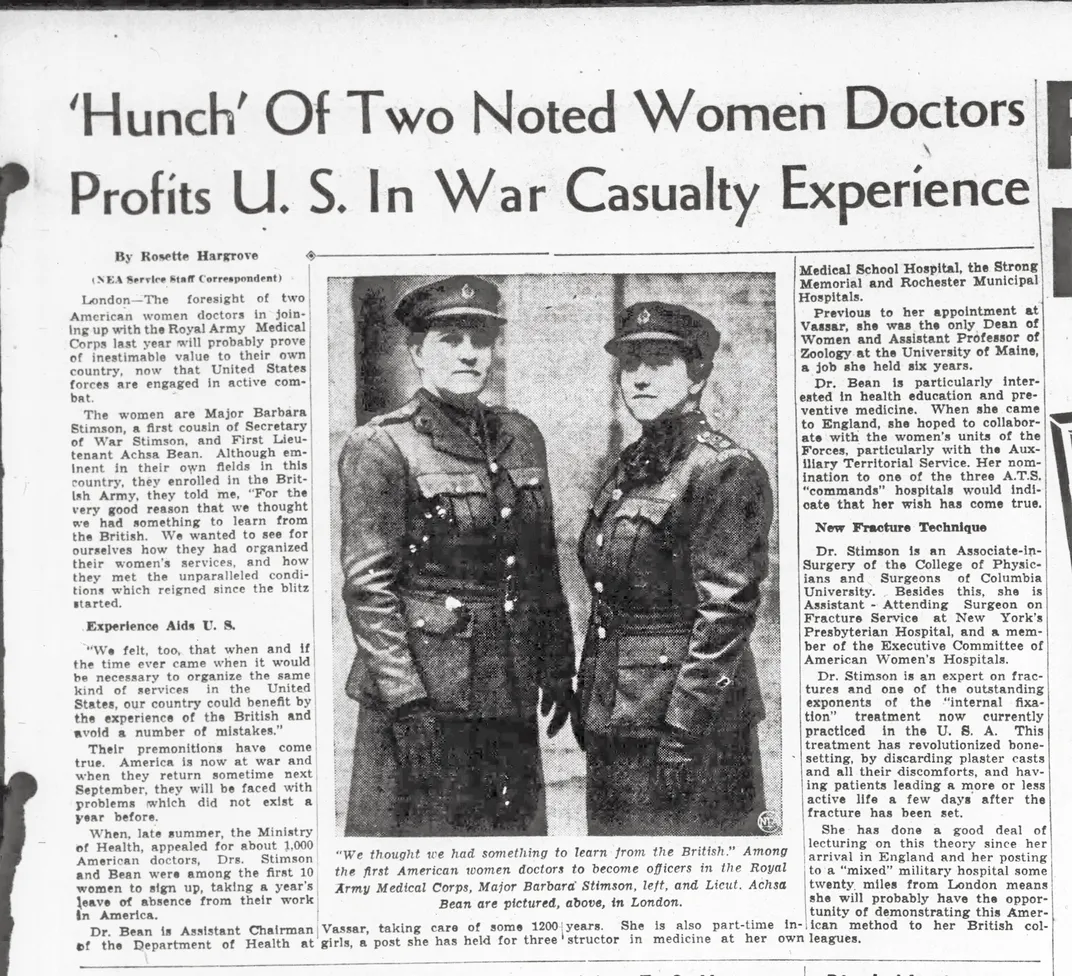

While a limited number of women physicians had been appointed to serve in the RAMC since 1939, no American women ever had. With help from Lady Astor and the American ambassador, John Gilbert Winant, they were commissioned on February 1, 1942. It took all of a week for the news to reach the American public. “Army Rank for Dr. B. Stimson: American Woman Surgeon Is Made a Major in British Medical Service,” the New York Times reported on February 8, 1942. Bean was ordered to a military hospital in York, and Stimson to Shenley Hospital outside London. At first, Stimson treated only civilian casualties, but that changed when hospital ships began transporting wounded soldiers from North Africa, where the Allies were battling the Axis powers. Stimson met several women medical officers, all Brits, including a pathologist and an anesthesiologist, but she was the only woman surgeon at Shenley. Described by one British officer as “a big, businesslike woman with a boyish bob and a keen sense of humor” in Women Doctors Today, Stimson proved popular at her first RAMC post. She served as the pianist in a classical trio and played bridge and table tennis. She even subbed in to a cricket game one day when the officers’ team came up one person short. A novice, she proved adept at fielding and throwing the ball. “To my amazement, it stopped the game,” she later wrote. “They apparently had never seen a woman throw overhand!”

Stimson proved to be adaptable in other ways. One day while she was conducting rounds, a soldier under her care said, “Major, the men don’t like to call you ma’am. Would it be all right if they called you sir?”

Stimson “smothered a smile,” she later wrote, and said yes. She remained “sir” for the duration of the war.

While at Shenley, Stimson was summoned by Elliott Cutler, the commanding officer of the U.S. Officer Corps in Europe. He told her that “the powers that be” did not like to see her in a British uniform, and he offered her a position in the U.S. Medical Corps. If she joined, she would lose her rank, since women could not be commissioned in the U.S. Army. She declined.

In the fall of 1942, Ambassador Winant, who had assisted Stimson’s quest to join the RAMC, solicited her support in trying to change the U.S. military’s attitude toward women doctors.

As secretary of war, Henry L. Stimson, Barbara Stimson’s cousin and 31 years her senior, worked closely with Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to formulate military strategy. According to Stimson, Henry had opposed granting commissions to women doctors. Winant hoped that a meeting with Barbara Stimson might persuade Henry to change his mind. She agreed, and in late December she sailed to New York.

“Babbie, I don’t like to see you in that uniform,” she recalled him telling her, upon seeing her in her British military attire when they met in Washington, D.C. “But you don’t give women doctors commissions in the U.S. Army Medical Corps,” Stimson answered.

The next morning, Henry drove Stimson to the Pentagon, where she informed military leadership, including General Brehon B. Somervell, head of logistics for the Army, that women physicians were well respected by their male colleagues in Britain and had integrated seamlessly into the RAMC. She shared statistics to demonstrate that women served as heads of hospitals, specialists and general practitioners.

A few months later, in April 1943, Roosevelt signed into law the Sparkman-Johnson Act, which authorized the U.S. Army and Navy to grant women physicians commissions in the medical corps for the duration of the war plus six months.

Finally, after the United States had been at war for a year and a half, women physicians were able to hold a rank in the armed forces. Though never officially credited with influencing the bill’s passage, Stimson had met with key leaders to make the case for allowing women doctors in the military. During hearings on the proposed bill, Representative Emanuel Celler of New York noted that Stimson had gone to Britain, “which availed itself of her exceptional talents and attainments as a physician, and she is now a major in the British Army.”

Bean, who had returned to the United States in the fall of 1942 to care for her ill mother, became one of the first women commissioned in the U.S. Naval Reserve. She was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1944.

After the act’s passage, Stimson was offered various positions in the U.S. Medical Corps, including as a gynecologist, but none allowed her to practice orthopedic surgery. She refused them all.

Back at Shenley, outside London, Stimson heard from colleagues that orthopedic surgeons were desperately needed in North Africa, closer to the front. Though her commanding officers hesitated to send her, by November 1943, she finally received her orders. “With tears in my eyes and butterflies in my stomach, I got into the car that was to take me to my next adventure,” she wrote home. She was off to the base hospital near the city of Algiers, where doctors stabilized wounded soldiers arriving on ambulance trains from the Sicilian campaign and shipped them out to England.

She was warned by the head of orthopedic surgery that her new commanding officer was “violently opposed to having a woman officer in his hospital.” The officer made his feelings known early. Instead of assigning Stimson to the senior officers’ quarters, he put her in a sparsely furnished room, and he excluded her from staff meetings. One night after a party, Stimson and the commanding officer happened to leave at the same time. “I gathered up my courage and thanked him for having me, since I knew he had not wanted a woman officer,” she later recalled. The next day she was moved to a nicely furnished room in the senior officers’ quarters.

From the base hospital near Algiers, Stimson was instructed to form a specialty unit in orthopedic surgery and have it ready to ship out to Italy. In the meantime, she and her team traveled to field hospitals close to combat areas, providing much-needed orthopedic care on grievously wounded soldiers. Stimson was expecting to leave for Italy, but the departure was delayed by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius on March 17, 1944. On April 11, she and her team finally traveled from Naples to the No. 70 British General Hospital in Pompeii, housed in a former orphanage, driving through swirls of ash and passing houses with gray particles piled up to window ledges like snow.

By now, the Germans had surrendered in North Africa, the Italians had surrendered, and the Allies were planning for the cross-channel invasion of Normandy in June. But on the Italian front, the Allies had run into tenacious German positions near the Abbey of Monte Cassino. Just transporting the wounded to the hospital in Pompeii proved perilous. No one was safe from enemy fire—not the wounded or the men who carried them, not the ambulance drivers and not the medics. More than 2,400 members of the RAMC, including physicians, laid down their lives during World War II. In Italy alone, 121 were killed.

“I had treated mangled limbs from the buzz bombs, from the retreat from France at Dunkirk and from the Sicily campaign when in North Africa, but none like that afternoon,” Stimson wrote of her first day treating casualties from Monte Cassino, the site of the bloodiest battles of the Italian campaign resulting in more than 54,000 Allied casualties.

It was during this onslaught of casualties that Stimson encountered what she later called “the hardest operation I have ever done.” After taking a much-needed break from the operating room, she returned to find a new patient—and “both legs from knees down were pulp.” The young Brit must have stepped on a land mine, she surmised, or had taken a direct hit from a shell. To save his life she would need to perform two above-the-knee amputations.

Stimson worked quickly, cutting across the tissue of the thigh and clamping bleeding vessels along the way. After tying off the femoral vessels, she sawed across the femur until the bone separated. With no time to waste, she turned to the other side and repeated the steps. She was saddened that her young patient would have to adjust to life as a double amputee, but, as she wrote to her sister, “I had no time to brood on it, for the patients kept coming.”

The Allies captured Monte Cassino on May 18 and liberated Rome on June 4, 1944. Stimson finished out the war in Rome, operating on the wounded until hostilities in Europe ceased on May 8, 1945. Stimson hadn’t achieved everything she set out to do. “It will be a lasting regret of the writer that she did not get frontline experience,” she wrote in 1946. There’d been limited opportunities to serve at the front, and when they arose she couldn’t be spared from her hospital duty.

In August 1945, Stimson was honorably discharged, receiving two distinguished military medals. George VI named her a Member of the Order of the British Empire, for “the energy, zeal and breadth of vision” she brought to the specialized orthopedic center she opened at the No. 70 British General Hospital. Military historians Judith Bellafaire and Mercedes Herrera Graf later recognized Stimson as a medical pioneer in Women Doctors in War, published in 2009.

After the war, Stimson returned to Columbia University to resume operating and teaching. In 1947, she moved to Poughkeepsie, New York, where she maintained a private practice. In 1959, she became the first woman president of the Dutchess County Medical Society and the first female member of the New York Surgical Society. Upon retiring in 1963, she moved to Owls Head, Maine, and lived with Bean and their two Norwegian elkhounds until Bean’s death in 1975. In 1986, Stimson, who was living with her sister Dorothy, died at the age of 88.

Reflecting on her wartime service overseas, Stimson was matter-of-fact. “There was no distinction made professionally between the sexes,” she later wrote, “The work was there to be done by whoever was fitted for it.”